James Grega

Senior Content Specialist

grega.9@osu.edu

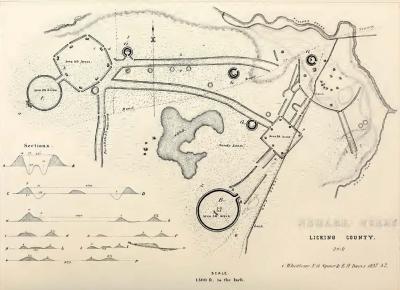

In 2023, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) added the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthwork sites, which includes the Newark Earthworks, to its world heritage list. It was the culmination of a decades-long push to get the Native American site officially recognized by UNESCO. The Ohio History Connection manages the Octagon Earthworks and two other Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks sites, while the National Park Service oversees the remaining five.

“In the last 10 years, massive amounts of research was done that helped explain how the earthworks were built, when they were built and really come to terms with how they are evidence of an indigenous civilization that was sophisticated, intellectually present, and learned and maintained knowledge over time,” said Marti Chaatsmith, associate director of the Newark Earthworks Center. “But the movement started in the 1980s.”

The earthworks at Newark are the making of the Hopewell Native American culture. Primarily, the earthworks were an observatory for tracking the moon and its long moon cycle. They were also likely used as ceremonial sites.

“It’s called the major lunar standstill, and that occurs only every 18.6 years, which translates to maybe 18 years and 200 plus days, a recurring cycle,” Chaatsmith said.

“The Octagon and High Bank earthworks in Ohio reflect a thorough understanding of cosmic (astronomical) movements observed from ground level over long periods of time.”

A major lunar standstill is when the moon rises and sets at a more northerly and southerly place along the horizon than usual, according to the Royal Astronomical Society.

“People who lived 2,000 years ago didn’t have extremely long lifespans,” Chaatsmith continued. “It says a lot about how they learned information and passed it on through generations and sustained it and learned more about it over time enough to build an enormous earthwork to track the long cycle.”

As for how they were built, Chaatsmith said that through research and analysis, we can assume the indigenous tribes traveled between 20 and 50 miles on foot, including to Zanesville and Coshocton, to supply the soil that it took to build the earthworks up to 30 feet high. It is estimated that they were built between 1,600 to 2,000 years ago, making it that much more impressive.

“The people that were building them understood that different kinds of soil and dirt had different kinds of qualities to maintain over time,” Chaatsmith said. “So, they went out of their way to find and learn about different kinds of dirt and soil, and to layer the earthworks as they built them.”

While the primary use for the earthworks was for tracking moon cycles, portions of the Newark Earthworks also served as burial grounds for the indigenous people. Unfortunately, once settlement started, settlers discovered there were valuables buried with the remains and began digging up the burial sites.

“People started to see that these places were special,” Chaatsmith said. “These mortuary sites were a baby step in archeology. The discipline of archaeology was beginning then. These sites became targets of looting, digging and so forth to bring up all of the items that were in the burials.”

Items found in the sites ranged from pounds of mica sheets, giant conch shells from the Gulf Coast, silver from the northern area in Canada and obsidian from the mountains out west.

“They were buried with the people, supposed to stay with the people,” Chaatsmith said. “For a long time, the sites were seen as treasure and then any earthworks that didn’t have burials were left alone or just plowed over.”

Fast-forward to the 1980s, when scholars started to take a serious interest in the Newark Earthworks. It was then that they confirmed its use as an observatory for the long moon cycle. From there, the momentum for global recognition of the earthworks started.

“A movement began at the grassroots level with support of The Ohio State University, the Newark Earthworks Center, the Ohio History Connection and their staff of archaeologists, and the archaeology community here, to save the sites and make them into one of the World Heritage Sites,” Chaatsmith said.

After a decades-long process that included a nomination, proposal and visits from UNESCO and the Department of the Interior, the official designation was finalized in 2023. For John Low, director of the Newark Earthworks Center and a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, the UNESCO World Heritage designation brings many positive emotions.

“There is a sense of shared accomplishment, relief, exuberance, giddiness and happiness,” Low said. “These indigenous sites that are of the same significance as Machu Picchu, the Giza Pyramids or the Taj Mahal, or the cathedrals of Europe or Stonehenge. We have the Newark Earthworks. I think that is really cool.”

For information about visiting the Newark Earthworks sites or taking a scheduled tour, visit the Ohio History Connection website.