Jen Farmer

Senior Marketing Manager

farmer.111@osu.edu

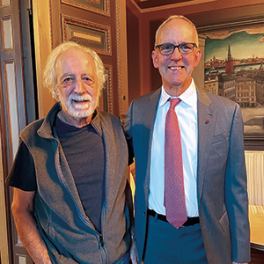

David Horn is an expert in cultural and historical studies of science and technology and currently serves as the dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. He joined The Ohio State University in 1990 as a faculty member to help build a program in science and technology studies in the Department of Comparative Studies. Through what he calls “a variety of happy accidents,” he ended up becoming the chair of the department relatively early in his career, while still an associate professor.

He served as chair for nine years and took on various roles at the university level — chairing the Steering Committee of the University Senate and serving as secretary of the Board of Trustees — before becoming associate executive dean for undergraduate education. Horn was appointed dean of the college in 2022.

What’s it like to lead the largest academic unit at one of the largest public universities in the country? We sat down with Dean Horn to learn more about his deep admiration for the arts and sciences, his advice for incoming students and recent graduates, and what he finds most rewarding and challenging about being an educator and college administrator.

Surprisingly, Horn never planned for a career in academia. In fact, his own college journey began like so many others — with excitement, trepidation, and uncertainty about what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

“I went to Amherst College, a small liberal arts college in Massachusetts. My family didn’t have the money to go around and do college tours, so I applied sight unseen. I chose Amherst because, among other things, they gave me the most generous financial aid. I had never set foot on the campus, and I didn’t know anybody else who had gone there. I thought I was going to be a doctor, but beyond that, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do in college. Somebody — I think my dad — told me to try an anthropology course, and that ended up being my major."

Though it might seem like it on the surface, his path to professor and college administrator wasn’t linear. He tried many things, including studying modern dance, before he decided to stick with what he loved — anthropology.

“The summer before my senior year of college, I went to an intensive summer dance program and also took the LSAT. I was considering whether I wanted to train for a possible career in dance, whether I wanted to go to law school, or whether I wanted to apply to graduate school in cultural anthropology. At some point, I decided

to keep doing what I was enjoying most, which was studying anthropology.”

The arts and sciences have always held a special place in his heart…

“I appreciate all the different ways my arts and sciences education both stretched me intellectually and opened me up to a wide variety of subjects. I took courses in poetry, music, sociology, political theory and philosophy. I expanded the set of questions that I was able to ask about the world around me, and I’ve continued to feel the power of the breadth and depth of the liberal arts.”

…and he believes the arts and sciences have never mattered more than they do at this moment in history.

“The world faces a wide variety of urgent challenges, and the research and creative projects that come out of our College of Arts and Sciences — whether from the arts and humanities, the social sciences or the natural and mathematical sciences — are crucial for asking productive questions and finding workable solutions. We prepare lifelong learners who are uniquely ready to navigate a rapidly changing economy and to move across barriers of language and culture. And because we are a land-grant university, we have an obligation to engage with local and global partners to intervene in the world in consequential ways.”

He understands the pressure that incoming students and their parents face to figure out what they want to do with the rest of their lives.

“There’s a lot of pressure on high school students and their parents to be thinking, from an early age, about what happens immediately after college. This sometimes pushes students to get degrees that have the same names as existing jobs, because it feels like everything’s going to be aligned. In the arts and sciences, you might be majoring in English or biology or history, but that doesn’t mean that you’re going to become a literary critic or a biologist or a historian. You might become a doctor or lawyer or elementary school teacher, or you might work for the government or a non-governmental organization. You might go into business, develop an app, or you start your own nonprofit. Almost anything is possible with a liberal arts degree and employers tell us over and over again how much they value that kind of preparation.”

And the experiences of our nearly 220,000 alumni provide him with the inspiration and conviction that the arts and sciences can be the right path for anybody.

“I spend a lot of my time on the road meeting with ASC alums, and the incredible variety of things they do is breathtaking. The passion of alums about their own undergraduate experiences in turn fuels the conversations I have with new students. If someone asks what they can do with an arts and sciences degree, I can point to some of the compelling stories I’ve been collecting from our graduates. And the stories are not just about their jobs — they’re about people who are leading meaningful and satisfying lives, and who are following all kinds of different paths. Some of them may be making a lot of money, and some may be earning a more modest income, but they’re all doing stuff that matters, to them and to others.

“Some of our alums talk about their education in terms of core competencies (to think critically or communicate effectively) and some emphasize the intellectual flexibility they acquired as students. Their time in our college gave them the ability to move fluidly from one thing to another, or to adapt themselves to jobs that didn’t even exist when they graduated. Others talk about their ability to ask generative questions, or to come at complex problems from many different angles.”

Hobbies

The thing I enjoy most is cooking, especially Italian and Chinese food. I don’t have as much time as I used to, but that’s how I relax at the end of a busy day.

Music Interests

I listen to wide variety of genres, and often get recommendations from our two sons. It’s fun when they sometimes discover the same bands that were important to me when I was their age.

Favorite Movie

I never tire of watching some of Alfred Hitchcock’s best films, such as Vertigo and Rear Window. I’m also a fan of the Italian director Paolo Sorentino.

Recent Reads

I’ve recently been enjoying historical novels: Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, which is set in 2nd-century Rome, and Orhan Pamuk’s My Name Is Red, set in the 16th-century Ottoman Empire. Both are beautifully written.

He has some wise words for our most recent graduates.

“Our graduates are told many things, some of which are helpful and some of which, unintentionally, produce added anxiety. One of the pieces of advice that I think produces the most anxiety is to be told, ‘Just do what you love!’ Even after graduating, a lot of people don’t really know yet what they love. And I think it’s important to remind our graduates that work isn’t everything. So, I would encourage recent graduates to think expansively about what their future is going to be. And to be patient, because the first job a person has right out of college is probably not going to be the last one. I’d say, ‘You’re going to find your path, and when you do, you’re going to be satisfied and happy in a broad and comprehensive way.’

“My own experience makes it look like I knew exactly what I wanted to do and then just did it, but it didn’t feel like that at the time. The more common route is to try different things, to learn from each of them, and to be better prepared for what comes next. Students should also be reminded that a lot of people have gone before them and faced similar challenges, and it has all worked out.”

He’s been at Ohio State for 34 years, and being dean of the College of Arts and Sciences has been the most enjoyable role of his career.

“What I like about being dean is not unlike what I enjoyed about being a department chair: bringing in new colleagues, developing new courses and degrees, thinking collectively about what kind of department we wanted to be and how we wanted to prepare students for life after college. In a sense, this is the work that I’m doing now, just at a different scale. While I don’t have direct involvement in imagining what each of our 38 departments and schools is going to become, I get to help generate resources and create opportunities for our academic units to sharpen their focus and increase their impact — to think about what it means to do the work they’re doing at a public land-grant university, at this moment in the history of the world and in the history of higher education.”

On a day-to-day basis, the people he works with are what he loves most about the job.

“I’ve got amazing colleagues in the dean’s office who are passionate about the work they do every day. I get inspiration from our department chairs and school directors. And I enjoy working closely with my student advisory board, faculty and staff advisory councils, and a Dean’s Advisory Committee made up of alums and friends of the college. They are all wonderful people who help us to think about where we’re going as a college and how to get there.”

The most challenging aspect of being dean of the largest academic unit at Ohio State is the obstacles that limit our ability to move quickly to advance our mission (and it’s probably not the first thing you’d guess).

“One of the principal challenges right now is our infrastructure. We have some buildings that are brand new, and you can readily see the work that these state-of-the-art spaces do to support our programs — the Timashev Family Music Building; the Theatre, Film, and Media Arts Building; and our renovated student chemistry labs in Celeste are a few great examples. And when you have the ability to reconfigure classroom spaces, students can interact differently and learn better. But when you don’t have excellent infrastructure, it really limits your ability to recruit and retain faculty and to provide students with the kind of learning experiences they deserve. Space is expensive and it also takes a long time to change it.”

But first and foremost, he’s still an educator at heart.

“The moments that have meant the most to me over the years are when I hear from students that I’ve taught in the past. They write to say that something we read together or talked about in class, even a dozen years ago, still matters to them or has led them to make particular choices in their lives. For me, that’s the most moving and satisfying part of my job.”