Underground History: Historic cemeteries tell stories of forgotten families

The Underground Railroad in North America, which helped slaves from southern states flee to northern states and Canada is an important story when telling America’s history. The journey south, however, is a story that is still being told.

María Esther Hammack, an assistant professor in the Department of History, is working to tell those stories and make sure the families involved have a voice.

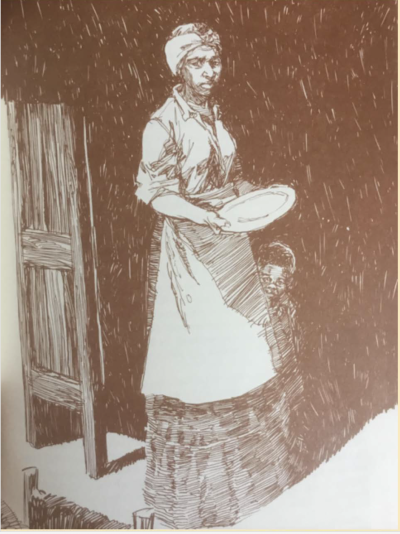

Hammack’s research began with the initial goal of finding “the Harriet Tubman of the south.” While she did find that person, a woman named Silvia Hector Webber, as well as her present-day descendants, Hammack’s work continues thanks to a Mellon Grant received last year.

“The Mellon Grant allowed us to not only do work on the Webbers, but to connect with other Afro descendants in the United States and in Mexico,” Hammack said. “We connected with an Afro indigenous community in northern Mexico in Coahuila called Los Negros Mascogos (Black Seminoles of Mexico) and their work to preserve their cemeteries. They need a lot of work. The tombstones are not even marked.”

The effort to preserve historic Afro indigenous cemeteries is not only to maintain the physical aspect such as headstones, which can often tell stories about local communities, but to also preserve legacies and tell the stories of the southern Underground Railroad that led slaves to Mexico.

“There are two main things that we're doing,” Hammack said. “One is connecting descendants to other descendants across the borderlands. In particular, the Webber family descendants to Afro descendants in México. The second thing we're doing is we're taking descendants from the Webber family and others to U.S. and Mexican archives where they learn how to do research and how to recover some of those stories through primary sources.”

Hammack said that teaching descendants to do their own discovery is important because while scholars are increasingly doing more exploration, they often aren’t able to tell the full story of a specific family or person. Through Hammack’s effort, she hopes to empower the descendants of historical figures like Webber’s to tell their family stories accurately through research.

“They can write their own books,” said Hammack, who wrote the first biography ever written about Silvia Hector Webber in 2019. “We're committed to be liaisons. We’ve facilitated meetings for descendants to speak to publishing presses and are organizing workshops so that editors can come and tell them how to propose a book, how to write it and how to utilize primary sources. And next year we are hosting two symposia to center and empower descendants. This way, families can tell their own stories and contribute to historical knowledge in a way that was previously much more uncommon.”

Just as it did in the beginning, Hammack’s research continues to evolve and bring up new question for the historian.

“The Underground Railroad to Mexico, it's not in question anymore, it happened,” Hammack said. “The question now is, what were the experiences of people that went to Mexico like? What did freedom look like in Mexico? Those are the questions that I'm trying to address.”

As Hammack continues to work in Mexico and the American Southwest, she said similar Underground Railroads are also being researched.

“When I was doing these stories, I spent a year in Canada with Fulbright because I wanted to learn about Canadian freedom before I could write about Mexican freedom,” she said. “What I found is we don't know as much about Canadian freedom as we think we know. When I was talking to descendants of people who went to Canada, I found a lot of erasures and descendants in Canada, today, are fighting to clarify things.”

Hammack hopes others who are in the same areas of study can learn from her work near the U.S.-Mexico border and apply it to their own research, including working with the families of those historical figures that first raised their interest.

“Be persistent, continue doing it,” she said. “That's one piece of advice. The second piece of advice would be when you're doing histories that are histories of recovery and preservation of legacies, particularly of black and indigenous actors, I think that it's very important to take into consideration descendants and their voices. In this recovery and preservation work that we’re doing, the descendants are integral.”