Blending history and memoir, Lindsey's 'America, Goddam' examines violence against Black women

As Treva Lindsey developed her upcoming book, she felt its initial title was missing something.

Then one day, Nina Simone spoke to her.

Nina Simone performs her protest song "Mississippi Goddam."

Simone recorded her first protest song “Mississippi Goddam” in 1964 after the assassination of civil rights activist Medgar Evers and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that killed four Black girls. As Lindsey contemplated the lyrics nearly 60 years later, the parallels between her book, the song and the world that sparked both became clear.

“‘America, Goddam’ is what came to mind,” said Lindsey, an associate professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies. “It’s that, ‘Goddamn, how are we still here? How are we still grappling with these same issues?’ … I think what is happening in the world charged me to write this book in the way Nina Simone was charged to write the song — as a result of the levels of violence she was seeing against Black people.”

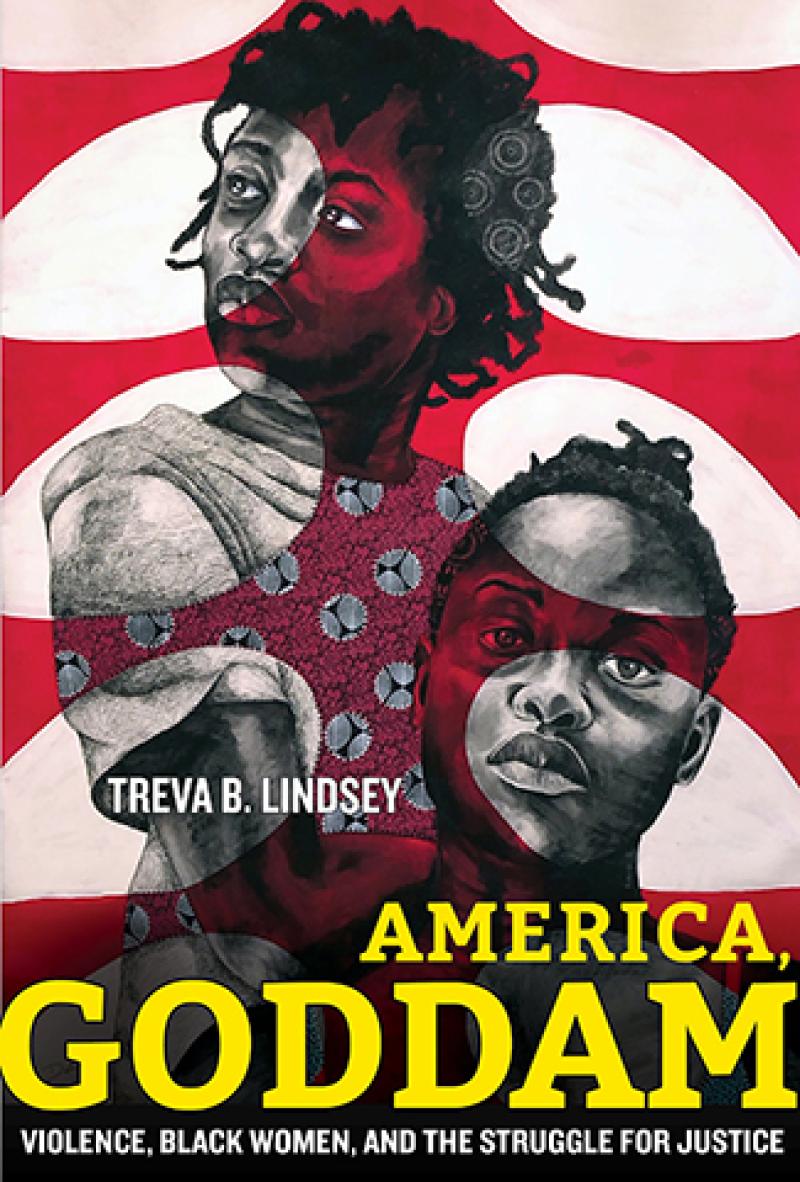

America, Goddam: Violence, Black Women, and the Struggle for Justice, set to publish April 5 by the University of California Press, explores how anti-Blackness, misogyny, patriarchy and capitalism have impacted Black women and girls. By weaving together scholarly commentary, historical research and personal memoir — all while backdropped by the violent deaths of Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Riah Milton and countless other Black women — America, Goddam paints a poignant picture of the lives cut short and the resistance to the forces that curtail them.

Lindsey sees herself in community with scholars, historians, activists and survivors of violence. While America, Goddam is rich in theory, history and research, Lindsey writes from the perspective of a survivor who has felt the impacts of the concepts she examines. Inspired by the Ntozake Shange poem for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, the book’s core asks how to hold Black women warmly and how to create a better world for them.

That blend of history, theory and memoir was the most honest way of telling the story,” Lindsey said. “The stakes of this work deeply matter to me, to the communities I’m in. This book is about bearing witness — on witnessing certain things. And on the other side, I’m also ‘withnessing.’ I’m with these stories. I sit with the pain of these stories, with the resistance. That balance of witnessing and ‘withnessing’ anchors the book and I hope gives the reader a sense of urgency and intimacy.”

Indeed, after an introduction in which Lindsey lays some historical and contextual groundwork, she invites the reader to join her as a child riding in her dad’s car, cruising around Washington, D.C., and listening to hip hop. Lindsey describes how her dad, who worked as a corrections officer and a probation officer, would sometimes pull lessons about racism and policing from the rap songs they’d nod their heads to together.

Lindsey continues to describe the violence of policing she saw throughout her childhood, how cops would cruelly handle unhoused people on her block, how they harassed her neighbors, how their overwhelming presence made her feel unsafe. When she began attending an elite private school in as a teenager, her white peers weren’t observed like that — even though she routinely saw underage drinking and drug use. By her sophomore year, Lindsey writes, she came to understand who the police protected and served and who they targeted and criminalized.

Though Lindsey discloses how anti-Blackness has impacted her, America, Goddam also focuses on and gives credit to the Black women who founded and led the most significant social movements of the decade, like #MeToo, #SayHerName and Black Lives Matter.

“Because of racism, sexism, misogyny and patriarchy, even the ways we come to understand certain moments historically have been impacted by who is telling those stories, who is centered in those stories and what voices remain unheard,” Lindsey said.

Lindsey doesn’t just recognize and center the Black women who are architects of these movements, but also the ones whose lives were stolen by anti-Black violence. Many only come to know those victims at their moments of harm. In the book, Lindsey identifies them by their first names, as women who are actively still loved.

In the book’s epilogue, Lindsey pens a letter to Ma’Khia Bryant, the 16-year-old Black girl shot and killed by a Columbus police officer on April 20, 2021. As details emerged, many discussions were quick to argue that the officer was justified because Ma’Khia had a knife.

“I was devastated by how people were talking about the case,” Lindsey said. “The threats I get to this day because I said she shouldn’t have been killed would alarm somebody. It was so hard for people to imagine that even a person with a weapon deserved to have her life protected.”

When Lindsey heard about Ma’Khia, America, Goddam was finished and in production. She was compelled to write an epilogue, so she contacted her editor and was given the green light. She sent a draft of the letter to Ma’Khia’s family, who gave their blessing for its inclusion.

“It was really me responding to this moment and the responses I’ve gotten for even wanting to respond to this moment,” Lindsey said. “It was a commitment to fighting for a world in which she would have lived — that everyone in that situation would have lived. … The letter asks a lot of questions, and it demands a lot of me and, hopefully by extension, anyone who’s reading.”