Department of Philosophy honors two pioneering Black philosophers

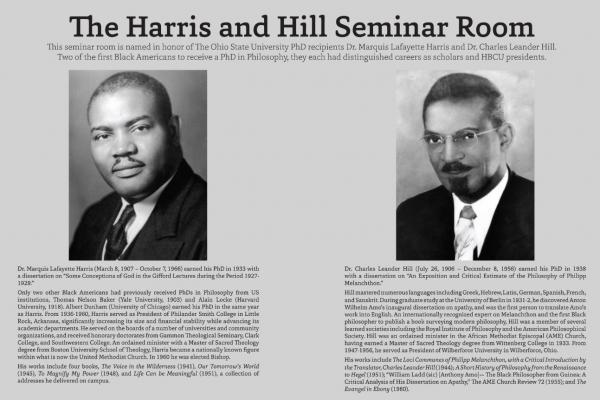

The Department of Philosophy honored Marquis Lafayette Harris and Charles Leander Hill, two of the first Black Americans to receive a PhD in philosophy, by renaming the 353 University Hall seminar room after these two Ohio State graduates last year.

Faculty, staff and students visit the Harris and Hill Seminar Room for meetings, graduate seminars, guest speakers and other opportunities to share in colloquia.

“That room is really the life of the department,” said Piers Turner, associate professor of philosophy and director of the Center for Ethics and Human Values. “To rename that room is to say that it’s important to us, as a department, that it be named after these two men.”

Turner first became aware of Harris and Hill when the Ohio State Office of Diversity and Inclusion mentioned they might deserve more attention for their lifelong accomplishments. He began researching the two PhD graduates, and the department approved the proposal to rename the seminar room in spring 2021.

Throughout the process of writing the proposal and creating the commemorative plaque for the seminar room, Turner collaborated with the Ohio State chapter of Minorities and Philosophy (MAP) as the group examines and addresses issues of minority participation in academic philosophy.

Turner wrote the text about Harris and Hill while Lavender McKittrick-Sweitzer ’21, president of MAP at the time, took the lead on creating an engaging design for the plaque.

Turner found it difficult to summarize the scope and scale of Harris and Hill’s accomplishments.

Harris preached at the Pennsylvania Avenue Methodist Church in Columbus for two years while he studied philosophy at Ohio State. He served as president of Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas, for 24 years, significantly improving the institution's reputation by expanding the campus and student population. Throughout his life, Harris was a board member for many universities and community organizations, including the National Council of Churches, the largest ecumenical body in the U.S., from 1944 to 1951.

Years before attending Ohio State, Hill studied as an exchange student at the University of Berlin in Germany. He was fluent in several languages, including Latin, and used that knowledge to transcribe Anthony William Amo’s inaugural dissertation on apathy, making him the first person to translate the Ghanaian philosopher’s writings from Latin to English, in addition to providing valuable commentary on philosophical teachings in Amo’s thesis. As president of Wilberforce University, Hill was displeased with the lack of educational resources on philosophy and created his own text for classroom instruction, becoming the first Black American philosopher to publish a book on the history of modern philosophy.

“Part of what’s interesting about this story is that they have similar trajectories in certain ways,” Turner said. “They both were philosophy graduate students, became presidents of these historically Black colleges or universities, but they also were both ordained ministers.”

Decades before there was a degree for anything a student could hope to pursue, ordained ministers more commonly earned philosophy degrees as it seemed a logical step in their theology training. Even Martin Luther King Jr. was a student of philosophy and taught philosophy concepts to college students.

For several years, the Department of Philosophy has turned more attention toward its diversity, equity and inclusion efforts to create an atmosphere where students and visitors of diverse backgrounds feel welcome. The increased initiatives have touched every corner of the department from recruitment efforts (Philosophy and Critical Thinking Summer Camp) to curricular revisions (guest lecturers from diverse backgrounds) to department culture (an open Philosophy in Race faculty position).

“It’s a field where we need to continue to be making really concerted efforts to continue to improve the pipeline and make the field attractive for a diverse group of students,” Turner said. “To look back at the 1930s and see that there were already these people coming into philosophy is a good lesson for us to figure out how we can, as a discipline, take steps to be as open as possible.”