Herbals: botanical bounty of the Renaissance book trade

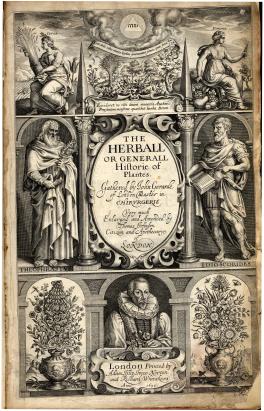

Herbals, a genre of books that contain information and illustrations about plants and their uses, dominated the print marketplace in England through the 16th and early 17th centuries. While we know plenty about the authors of these herbals, what do we know about the people who were publishing and reading these botanical books?

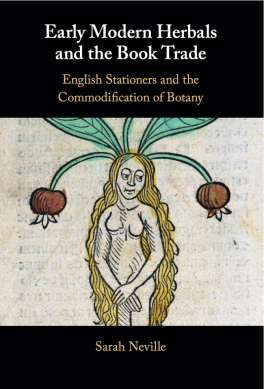

It’s a question that Ohio State Associate Professor Sarah Neville explores in her book “Early Modern Herbals and the Book Trade,” which focuses on the growth of herbals between 1525 and 1640 in England and how the print market adjusted to accommodate the popularity of these plant publications.

“The study of plants and animals in the world around us needs to be as much a study of the people who disseminated that knowledge as it is the people who were the authors of that knowledge,” Neville said. “I'm really interested in the way that information makes it to the public so that it can become known, because it’s things becoming known that enable people to become authorities.”

Neville began her research as an undergraduate at the University of Toronto. Enrolled in a course on early modern linguistics, she was first introduced to herbals and became interested in how books were made and sold in that period. While markets for some books – namely religious texts and law books – existed in England at the time, Renaissance publishers, like publishers today, had to take on some economic risk as they introduced new kinds of texts to the reading populace.

“The people who made books in the period didn't throw money around,” she said. “They're entrepreneurs because they have to speculate. It's the stock market. For example, I have the rights to print ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ and I'm going to print my 700 or 800 copies of this text, and if it sells out, I’ll print it again. Because I own the right to print that book, I can control the reading market for it.”

As for what made the books so popular, readers used them to learn about local plant life and potential uses, ranging from medicinal purposes to warding off spirits, though Neville noted that readers did not believe everything simply because it was written down. But in addition to learning, readers also took the opportunity to add in their own knowledge.

“People would annotate herbals with information about their local environment and so you'll see that sort of handwritten notation in the margins,” she said. “I think that what's happening is that these books served a function in a historical moment for many, many people, and then the books got used so frequently they fell apart. Like my grandmother's recipe books that got used to pieces, they're doing the same sort of thing.”

These herbals were popular among everyday people, but other literary works show that they also made their way into the hands of the elites at the time, too. John Milton’s poem “Paradise Lost,” published in 1667, focuses on Adam and Eve and their eventual banishment from the Garden of Eden after disobeying God and eating the forbidden fruit.

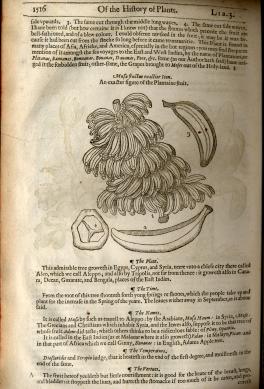

While neither the Bible nor Milton explicitly name the fruit, Milton’s description – implied to be a banana, according to Neville – matched that of herbals from the time, including those of English herbalist John Gerard.

“Milton’s lifting from one of these great big herbals that tells all of these stories about plants and describes them in detail, that’s the same herbal that I studied when I was an undergrad,” Neville said.

Along with her work in the Department of English, Neville has a dual appointment with the Department of Theatre, Film and Media Arts, where Shakespeare is among her key scholarly endeavors, and she serves as the creative director of Lord Denney’s Players, a theatrical group at Ohio State that uses performance-as-research. In connecting her distinct roles, Neville – like she does with her research into herbals - considers all audiences as they connect with Shakespeare’s work at the time.

“We tend to implicitly associate Shakespeare with the fanciest of knowledge, whereas Shakespeare is a country boy from Stratford-upon-Avon, running around, knowing the environment,” she said. “He's not coming up with an elaborate explanation for what a plantain [a type of English weed] is. He's often coming up with the most banal one.”

“Early Modern Herbals and the Book Trade” is available as an open-access ebook through Cambridge University Press. The publication was made possible through the Ohio State Open Access Monograph Initiative, a program run by Ohio State University Libraries that publishes books by faculty.

“Open Access is cool, because I can see my book is in public libraries throughout the world, and that is unbelievable, because normally books of this kind have a handful of readers,” Neville said. “What that means is that people have reached out to me who otherwise wouldn't have read an academic book like this from Cambridge at all.”